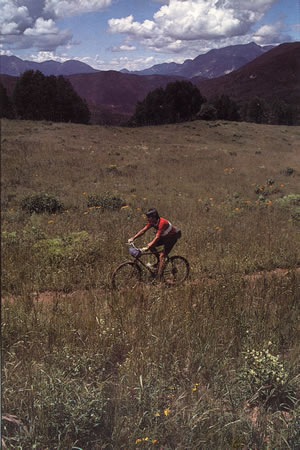

Bicycles belong in wild places.

Bicycling and Wilderness

Why Bicyclists should be allowed on some trails in some Wilderness*

by Jim Hasenauer

Mountain bicycling is a human powered, environmentally sustainable, outdoor recreation that is compatible with the philosophy, history and future of Wilderness. Mountain bicyclists are drawn to wild places, to exploration, to self sufficiency and to traveling under their own power through challenging terrain.

The ban on bicycles in Wilderness is philosophically and historically flawed. It harms a significant number of bicyclists who are being discriminated against. It weakens the environmental and outdoor recreation communities and therefore reduces protection of wild places. Lifting the system-wide ban and creating regulatory language that would allow bicyclists on some trails in some Wilderness is the best public policy.

Philosophical Justification

Early wilderness proponents were alarmed that the automobile, auto tourism, and an expanding infrastructure to serve those tourists were rapidly penetrating the wild, undeveloped landscapes of the United States (Sutter, 2002)1. As trains had transformed landscape and public policy in the 1800's, the automobile was doing the same in the early 20th century. Road construction was opening up remote areas. Public work programs concentrated many of these efforts on America’s public lands and access provided an explosion of sightseeing and car camping opportunities. Tourists once arriving at some natural wonder would be offered “rides” on wagons, cars on tracks, or some other infrastructure. This was called “mechanized recreation” and these early wilderness advocates saw that if protections were not put in place, the breadth of wildlands would be significantly diminished.

There was also a puritanical and romantic conception of these landscapes that was tied to an idealization of pre-Colonial Native American and early American frontier life. These early wilderness proponents like Leopold and MacKaye valued recreation that required strenuous effort, self sufficiency, and an element of danger. The 1964 Wilderness Act memorialized this philosophy.

Mountain bicycling is philosophically consistent with Wilderness designation. Bicyclists seek out natural surface trails, not roads; they exert their own human power to navigate this terrain; they are drawn to the solitude and natural splendor of wildland; they must be competent and self sufficient or they put themselves at great risk.

Historical Justification

Some people think that bicycles are banned from Wilderness because they are machines, but the legislative and regulatory history does not bear that out. Bicycles are machines, but (as is discussed on this site) only in the way that oarlocks, hiking poles, ski bindings, some climbing equipment, kayak rudders or even soft-soled shoes are. They lever human effort, but ultimately they are human powered, not “propelled by a non-living power source” as 1966 Wilderness regulations define “mechanical transport”.

The 1964 Wilderness Act did not ban bicycles from Wilderness; 1984 regulations did. It’s likely that at the time, that ban was merely one of several instances of hiking and environmental organizations exerting their influence on public land policy. They were wary of the emerging number of mountain bicyclists showing up on trails on US public lands. From 1981 through the early 1990's, restrictions on bikes or outright bans were implemented on city and municipal parks, regional and state parks, and across the various federal land management agencies. While mountain biking was a new activity on public lands, the arguments supporting the bans and restrictions were always the same: bikes caused environmental damage, bikes were unsafe in the trail user mix, and bikes were a modern piece of equipment philosophically incompatible with backcountry recreation.

When mountain bicyclists organized to deal with these bans and to participate in management regulations, each of the arguments above was examined and in most cases it has been found that mountain biking is a safe, sustainable activity on trails on public lands. Most of these early bans have been reversed and regulations have been changed to allow bicycle access. The mountain bike community has proven itself to be a legitimate, responsible, and positive user group on public lands. Nonetheless, the Wilderness ban has persisted.

The 1984 regulation which banned mountain bicycles from Wilderness is an historical artifact. It’s a vestige of early caution and even fear and hostility toward an emerging recreational use. As Stroll (2004)2 observed, with the Forest Service, keeper of the greatest Wilderness acreage, the ban on bikes was contested and confusing as contradictory regulations were introduced between 1977 and 1984.

The 1984 ban is anachronistic, an indication of prejudice and lack of accurate information at the time. The ban should be lifted and a new regulation modeled on an earlier 1981 regulation that empowered land managers to generally allow, but specifically prohibit bicycle use in some areas of Wilderness should be re-instated. This new regulation would offer a best practices, fact-based decision making model for mountain bike recreation in designated Wilderness.

Political Justification

Wilderness needs all the help it can get. In our current age, the concerns of early wilderness proponents about automobiles, roads and development are magnified by threats driven by economic motives. Strong efforts from mining, timber, public utility and other economic interests, some of which are associated with national defense, threaten the natural systems of wild places. Sometimes Wilderness advocates will try to designate an area to specifically block some planned commercial incursion into wild places. These battles are difficult and often pit the intellectual resources of environmental policy experts and the masses of generally identified “environmentalists” against the persistent lobbying efforts of commercial enterprise. The anti-Wilderness forces are bolstered by motorized recreation enthusiasts and a variety of property rights advocates concerned about government ownership and regulation of lands. These battles are resource intensive and difficult.

Mountain bicyclists often find themselves as a sidebar skirmish in these larger battles. When new Wilderness areas are proposed, bicyclists look to see if trails they ride are included and then attempt to negotiate with Wilderness proponents to exclude those trails or find another designation to protect the land. The Wilderness proponents often are annoyed at what they consider to be last minute attempts to change well researched public land protection schemes. In realpolitik terms, the bicyclists are cast as an enemy of Wilderness. Too often, resentments, and frustration emerge on both sides. Trust is destroyed. What should be a common constituency with common interests is divided. Wilderness advocates and bicyclists become antagonists.

This does not have to be the case. There are some 40 million mountain bicyclists in the United States. They share a love of wild places and could be mobilized as a constituency for Wilderness, a Wilderness with regulations that saw them for whom they were. We have often been asked, “What’s more important, land and habitat protection or bicycle recreation?” That’s a false dilemma. We can have both. We should have both.

*As has become the custom in the mountain bike community, upper case “Wilderness” refers to designated Wilderness areas. Lower case “wilderness” refers to natural terrain and habitat in wild, undeveloped places.

1. Sutter, Paul, Driven Wild: How the Fight Against Automobiles Launched the Modern Wilderness Movement;University of Washington Press; 2002.

2. Stroll, Ted, "Congress's Intent in Banning Mechanical Transport in the Wilderness Act of 1964," Penn State Environmental Law Review; Autumn, 2004; 12:3; p.459.